Toxoplasma gondii es una

especie de

protozoo parásito causante de la

toxoplasmosis, una enfermedad en general leve, pero que puede complicarse hasta convertirse en fatal, especialmente en los

gatos y en los

fetos humanos.

1 El

gato es su hospedador definitivo, aunque otros animales

homeotermos como los humanos también pueden hospedarlo.

Fuentes de infección

La fuente de infección más frecuente no son los animales de compañía como erróneamente se cree y se sigue difundiendo sin base científica.9

La realidad es que la fuente por la cual entra el parásito en los humanos con mayor frecuencia es a través de los alimentos contaminados: la carne (cuando está poco cocinada, ya que un gran porcentaje está contaminada) y las frutas y verduras mal lavadas.

10

De las carnes disponibles para consumo en el mercado (o las carnes de caza), un gran porcentaje de todas las especies está contaminado, así que cualquier persona que consume carne ha consumido (de hecho) carne contaminada por el parásito. También es posible que por la manipulación de la carne contaminada con las manos, al llevarlas a la boca, se ingiera el parásito.

Por otro lado, una persona que consume con la necesaria frecuencia verduras y frutas, puede consumirlas sin el adecuado lavado para eliminar el parásito en algún momento. También puede consumidas manipuladas por terceros sin poder supervisar si el lavado es suficiente (por ejemplo, en restaurantes).

El ciclo vital de

Toxoplasma tiene como huésped definitivo al

gato o miembros de su familia, que tras ingerir alguna de las formas del parásito sufre en las

células epiteliales de su intestino un

ciclo asexual y luego un

ciclo sexual, eliminándose en sus heces millones de ooquistes. Cuando estos esporulan se vuelven infecciosos pudiéndose infectar otros animales por su ingestión. Por debajo de 4 °C, o por encima de 37 °C, no se produce la esporulación y los quistes no son infecciosos.

Los humanos sufren la transmisión del parásito fundamentalmente por vía oral a través de la ingesta de carnes, verduras, el agua, huevos, leche, u otros alimentos contaminados por ooquistes o que contienen quistes tisulares. De hecho, hasta un 25% de las muestras de carnes de cordero y cerdo presentan ooquistes, siendo menos frecuentes en la carne de vaca. Los gatos, sobre todo si se manipulan sus excreciones, pueden infectar al ingerir los ooquistes por las manos contaminadas.

La última vía de contagio suele producirse entre personas que trabajan la tierra con las manos, bien agricultores, bien en labores de jardinería. En los suelos suele estar presente el parásito en gran cantidad. Una persona que manipule la tierra con las manos desnudas puede introducir restos de tierra bajo las uñas. Pese a un lavado de manos con agua y jabón, siempre puede quedar tierra bajo las uñas. Después, si se lleva las manos a la boca, es fácil infectarse de éste y/o de otros parásitos. Si es una persona que trabaja en el campo, no tiene por qué lavarse las manos cada vez que manipula esa tierra y en un descuido (o por mala costumbre) puede llevarse las manos sin lavar a la boca.

Siempre se ha relacionado erróneamente al gato doméstico como fuente de infección, puesto que sí son los hospedadores definitivos junto con otras especies de felinos. El error se basa en que el comportamiento humano necesario para esta infección no es el "normal".

Para que un gato pueda producir heces infecciosas tiene que contagiarse. Es decir, un gato que no está infectado y vive en una casa sin acceso al exterior y comiendo pienso o carne cocinada, no puede infectarse y por tanto no puede infectar a otros.

Si el gato tiene acceso al exterior o es silvestre, o come carne cruda, o caza pájaros o ratones y se los come, entonces sí puede infectarse.

Una vez infectado, incuba el parásito durante un periodo de entre 3 y 20 días (según la forma en la que lo ingiere, que determina la fase en la que se encuentra el parásito). Después y durante sólo un periodo de 1 mes, libera los ooquistes en las heces. Después de eso, aunque se vuelva a infectar, nunca más liberará ooquistes.

Para que esas heces con

ooquistes (

oocitos) sean a su vez infecciosas, necesitan un tiempo de exposición al medio de entre 24 y 48 horas. Las personas normales que conviven con gatos en casa suelen retirar las heces de los areneros con más frecuencia, impidiendo que esos ooquistes maduren y sean infecciosos. Y después, es necesario un contacto muy íntimo con esas heces para infectarse a partir de ellas. Es necesario comerse las heces del gato para infectarse (cosa que sólo hacen los niños o personas con enfermedades mentales) o si no, manipularlas con las manos y sin guardar unas mínimas medidas de higiene, llevárselas a la boca. De nuevo citamos a la "gente normal" que si tiene que realizar una limpieza de heces, de gato o de cualquier animal, después procura lavarse las manos con agua y jabón. No sólo se puede introducir el Toxoplasma Gondii en el organismo de esta manera, también otros parásitos, bacterias y virus, mucho más peligrosos e incluso letales en ocasiones como la

Escherichia coli.

Por tanto, cualquier persona que conviva con un gato o varios como mascotas, incluso con acceso al exterior y hasta que coman a veces animales crudos cazados por ellos (es decir, gatos con riesgo de infectarse del parásito), con la más simple medida de higiene posible (el lavado de manos después de limpiar el arenero o usando guantes), evita infectarse del temido Toxoplasma.

Por razones desconocidas se sigue obviando la dificultad de esta ruta de infección (pese a los intentos que los profesionales veterinarios realizan de informar a la población propietaria de gatos y de concienciar a los médicos de la necesidad de dar información científica y no una información sesgada e incorrecta).

Se sabe que el parásito cruza la

placenta pudiendo transmitirse al feto, si la madre se infecta por primera vez durante el embarazo. Si la infección ocurrió antes de quedar embarazada, el nuevo bebé no puede ser infectado.

11 El riesgo es menor si la infección ocurrió en las últimas semanas de gestación. Con muchísima menos frecuencia, el parásito puede ser transmitida por

transfusión de sangre, o

trasplante de órganos.

En los casos en que se detecta que una mujer gestante se ha infectado del parásito, existen medicamentos que pueden ayudar a detener la infección para evitar daños al feto.

Contenido

Morfología

Ooquiste

Un ooquiste es la fase

esporulada de ciertos

protistas, incluyendo el

Toxoplasma y

Cryptosporidium. Este es un estado que puede sobrevivir por largos períodos de tiempo fuera del hospedador por su alta resistencia a factores del medio ambiente.

Bradizoíto

El bradizoíto (del

griego brady=lento y

zōon=animal) es la forma de replicación lenta del parásito, no solo de

Toxoplasma gondii, sino de otros protozoos responsables de infecciones parasitarias. En la toxoplasmosis latente (crónica), el bradizoíto se presenta en conglomerados microscópicos envueltos por una pared llamados quistes, en el

músculo infectado y el tejido cerebral.

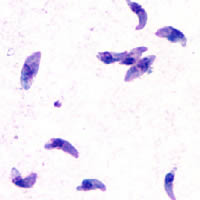

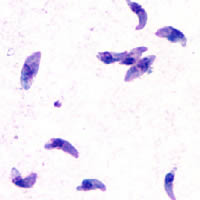

2 Taquizoito

Los taquizoitos son formas mótiles que forman quistes en tejidos infestados por toxoplasma, y otros parásitos. Los taquizoitos se encuentran en vacuolas dentro de las células infestadas.

Ciclo de vida

Ciclo vital de

Toxoplasma.

El

ciclo de vida del

T. gondii tiene dos fases. La fase

sexual del ciclo de vida ocurre solo en miembros de la familia

Felidae (gatos domésticos y salvajes), haciendo que estos animales sean los hospedadores primarios del parásito. La fase

asexual del ciclo de vida puede ocurrir en cualquier animal de

sangre caliente, tales como otros

mamíferos y

aves. Por ello, la toxoplasmosis constituye una

zoonosis parasitaria.

3En el hospedador intermediario, incluyendo los felinos, los parásitos invaden

células, formando un compartimento llamado

vacuola parasitófora

4 que contienen

bradizoitos, la forma de replicación lenta del parásito.

5 Las vacuolas forman

quistes en

tejidos, en especial en los

músculos y

cerebro. Debido a que el parásito está dentro de las células, el

sistema inmune del hospedador no detecta estos quistes. La resistencia a los

antibióticos varía, pero los quistes son difíciles de erradicar enteramente.

T. gondii se propaga dentro de estas vacuolas por una serie de

divisiones binarias hasta que la célula infestada eventualmente se rompe, liberando a los

taquizoitos. Éstos son mótiles, y la forma de

reproducción asexual del parásito. A diferencia de los bradizoitos, los taquizoitos libres son eficázmente eliminados por la inmunidad del hospedador, a pesar de que algunos logran infectar otras células formando bradizoitos, manteniendo así el ciclo de vida de este parásito.

Taquizoítos de

Toxoplasma gondii teñidos con

tinción de Giemsa, a partir de una muestra de líquido peritoneal de ratón.

En

1908, Nicole y Manceux demuestran la presencia del parásito en un

roedor el Ctenodactylus gondii.

Toxoplasmosis

Las infecciones por

T. gondii tienen la facultad de cambiar el

comportamiento de

ratas y ratones, haciendo que se acerquen, en vez de huir del olor de los gatos. Este efecto es de beneficio para el parásito, el cual puede reproducirse sexualmente si es ingerido por el gato.

6 La infestación tiene una gran precisión, en el sentido de que no impacta los otros temores de la rata, tal como el temor de los espacios abiertos o del olor de alimentos desconocidos. Se ha especulado que el comportamiento humano puede igualmente verse afectado de alguno modo, y se han encontrado correlaciones entre las infecciones latente por

Toxoplasma y varias características, tales como un aumento en comportamientos de alto riesgo, tales como una lentitud para reaccionar, sentimientos de inseguridad y

neurosis.

7

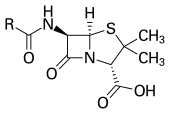

T.gondii es un parásito intracelular con un

citoesqueleto probablemente especializado para la invasión de células que parasitar. En azul YFP-α-Tubulina, en amarillo mRFP-TgMORN1.

Para la prevencion de la

toxoplasmosis congénita en mujeres embarazadas se recomienda la

espiramicina, ya que es menos

tóxica. Este medicamento evita que los taquizoitos pasen el lago

placentario hacia el feto. Si el parásito ya ha atravesado la placenta ya no es eficaz, aunque parece tener beneficio disminuyendo la carga parasitaria y por lo tanto disminuyendo la severidad de los síntomas en algunos casos.

8 En inmunodeficientes se recomienda la combinación de pirimetamina con sulfadiazina, pero dada la mayor posibilidad de los pacientes infectados con VIH de alergia a las sulfas, en ocasiones es necesario usar la combinación de pirimetamina con la

clindamicina.

Cuadro clínico

La etapa aguda de las infestaciones por toxoplasmosis pueden ser asintomáticas, pero a menudo aparecen

síntomas gripales que conllevan a estadios latentes. La infección latente es también, por lo general, asintomática, pero en personas

inmunosuprimidas (pacientes

trasplantados o con ciertas infecciones), pueden mostrar síntomas, notablemente

encefalitis, que puede ser mortal.

Varía dependiendo en qué trimestre del

embarazo se adquiera el parásito:

- 1er trimestre: muy probablemente la muerte fetal intrauterino.

- 2do trimestre : el bebé nace con malformaciones.

- 3er trimestre: secuelas, afecciones graves del sistema nervioso central, hidrocefalia, se reproduce en las paredes de los ventriculos, hay peligro de que el tejido necrosado obstruya el acueducto de Silvio, calcificaciones cerebrales, aspecto de niño prematuro, hepatoesplenomegalia, ictericia, neumonitis, miocarditis.

La toxoplasmosis en embarazadas es rara vez sintomática pero puede provocar: linfadenopatía,

fiebre,

mialgia, malestar general, entre otras.